Ransomware is one of the most harmful and costly cyber threats in existence, with potentially devastating consequences. In May 2021, the DarkTrace ransomware attack on the Colonial Pipeline forced the shutdown of all pipeline operations that transport approximately 400 million liters per day of gasoline, causing the U.S. Department of Justice to elevate ransomware attacks to be on a par with terrorism.3 In the same month, Conti ransomware conducted a cyberattack against Ireland’s Health Service Executive, which provides all the country’s health services. The incident was not discovered until two months after the ransomware initially gained access and it finally delivered its payload. General health services5 were severely disrupted and the personal data of hundreds of thousands of people was stolen. Ransomware is a daily threat to individuals, companies, organizations, and states alike. The attack surface covers all digital infrastructure—information technology (IT) and operational technology (OT)—extending to industrial control systems (ICS), passing through the software supply chain, and cloud providers.

Key Insights

The ransomware ecosystem has significantly evolved, leading to profound changes in extortion practices.

This study provides a comprehensive overview of the tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) observed in ransomware campaigns.

Ransomware—and cyber threats more broadly—should be studied systematically, taking into account technical, human, organizational, and political dimensions.

The attack surface has expanded dramatically, affecting individuals, SMEs, large enterprises, and public sector institutions alike.

All sectors are targeted indiscriminately (including critical infrastructure), and in particular healthcare and medical, education, emergency services, energy, public and government facilities, financial services and markets, and transportation. In July 2023, the port of Nagoya, one of Japan’s busiest, was forced to cease operation for two days owing to a ransomware attack attributed to LockBit. Many countries are also targeted by ransomware attacks. In 2022, several government services in Latin America (LatAm) were affected by ransomware attacks.18 In 2024, hundreds of small Indian banks went offline due to the RansomExx attack. That same year, South Africa’s National Health Laboratory Service (NHLS) was disrupted following a BlackSuit attack, and Australian telecommunications giant Optus suffered a major data breach, with a ransom demand.

While the list of big game hunting ransomware attacks that make the headlines is long, the fact of the matter is that many attacks are opportunistic. They target individuals and small organizations,7,16,34 which are less protected, in the form of more silent attacks but with sometimes dramatic consequences.

What is going on behind the scenes of ransomware? What comes to mind is a malware that encrypts victims’ assets, such as files, databases, and backups. Computer services are locked and demands for payment are made in exchange for restoring access thereto. In 2017, WannaCry spread automatically to nearly five million vulnerable devices in what Europol called an “unprecedented” event. WannaCry is a typical example of a commodity ransomware.

The ransomware ecosystem has evolved in recent years.25 Ransomware campaigns are primarily human-operated within a versatile dark ecosystem that provides services and sells information. Before encrypting victims’ files, sensitive information and simple data are exfiltrated, some of which may be disclosed on data-leak sites. In the negotiation stage, ransomware actors use blackmail tactics, threatening to reveal compromised data either publicly or to victims’ partners, and even putting pressure on victims by distributed denial-of-service (DDOS) attacks. These practices are known as double and triple extortion, respectively.

Rather than talking about ransomware, a term such as extortionware would better describe the issues and the criminal ecosystem we are facing. The activities of threat actors and the underlying economic model evolve, using all the technology at their disposal, despite constant pressure from international law enforcement agencies. We are far from the earliest recorded attacks, such as the AIDS Trojan horse in the late 1980s. The overall objective is financial, and data encryption to get a ransom is, of course, one way for threat actors to achieve their goal. However, there are other means, such as data exfiltration and harassment.

In this context, Ransomware-as-a-service (RaaS) is the dominant model in this ecosystem, which could be seen as a resilient web of disparate threat actors sharing resources and infrastructure. This evolution reflects a shift toward a relative maturity and professionalization of the cybercriminal ecosystems. The war in Ukraine affected the ransomware world, which is a testament to the relative porosity between ransomware actors and actors closely linked to states. Indeed, the reality of what ransomware encompasses is evolving under the influence of three key factors: geopolitics, threat actor organizations, and coordinated law enforcement responses to dismantle ransomware and underground networks.

Hence, ransomware should be investigated as a whole, which encompasses ransomware ecosystems; the overall impact on states, businesses, organizations, and individuals; and the tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTP) most used to conduct an attack, incorporating negotiation and human factors. This article focuses on these three aspects and relies as much as possible on information from peer-reviewed academic papers, national and international organizations, and the international press, supplemented by reports from cybersecurity companies and expert blogs. State organizations include the European Union Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA), the Agence National de la sécurité des systèmes d’information (ANSSI), the German Federal Office for Information Security (BSI), the Netherlands National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC-NL), the U.K. National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC), and the Australian Cyber Security Centre (ACSC). In North America, these include the Canadian Centre for Cyber Security, the Cybersecurity & Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), the National Security Agency (NSA), as well as law enforcement agencies European Cybercrime Centre (Europol-EC3) and the Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3-FBI). In addition to this article, there exist several state-of-the-art reports that review academic literature and explore defenses against ransomware21,29 or that focus on ransomware incident responses.2 Due to the nature of the sources consulted, the perspective of this article is predominantly focused on Western viewpoints and thus does not claim to fully represent the diverse circumstances of all countries globally. One final note: The lack of truly reliable and comprehensive data on cyber incidents36 is regrettable, as it hinders academic research, and this article inevitably suffers as a result.

Ransomware Ecosystem

RaaS model. What is behind ransomware groups such as REvil, Darkside, Conti, Lock-Bit, and RansomHub? Today, the trend in cyberattacks has shifted toward human-driven ransomware campaigns, making them more flexible and effective. There is a consensus that the RaaS model encompasses virtually all facets of the cybercriminal underground economy and organization. That said, ransomware groups may have different organization models as in the case of Royal.30 The landscape is schematically defined by two types of organizations: “opportunistic” organizations and “corporate-like organizations” with a business model exemplified by the Conti group. Indeed, what goes on under the hood is rather heterogeneous, with inevitable rivalries involving multiple actors in a highly versatile and criminal ecosystem comprising both organized groups and isolated actors.

Ransomware groups employ different strategies. Some, like Dark Angels until recently, choose to stay under the radar; others, such as LockBit and BlackCat, actively seek attention and public exposure. Leaks allow us to have first-hand testimonies. Owing to a disagreement about the payback of an affiliate, there was a leak in 2021 of an underground cybercrime forum named XSS related to Conti activities. The following year, there was a second leak of Conti papers,25 this time due to a disagreement following pro-Putin statements made by some members of the group. Threat actors are also interviewed and intelligence studies supplement information sources.

Regardless of the type of organization or strategy, the RaaS model provides scalable infrastructures, services, tools, and technologies to facilitate cybercrime. Different related groups contribute to this underground market. At the bottom of the ladder are affiliates, which are usually the ones launching the deadly payload to the victim. The Conti group is estimated to have around 100 members and a business-like structure. There are groups working on software development, the recruitment of new employees, financial negotiation, and revenue laundering. All this reveals a landscape in which there are core groups competing and working with other groups and hiring not only affiliates but also individuals to outsource one task or another. Affiliates have access to the ransomware infrastructure, for example a Tor-based control panel for managing victims and facilities to conduct a campaign.

Profits are shared and typically a payment of about 70% of the ransom is promised to the affiliates. It is common for affiliates to change groups because they are disappointed by technical difficulties and lower-than-expected revenues, like in the case of BlackCat’s affiliates.17

RaaS services and infrastructure. Ransomware threat groups develop tools, in particular for managing affiliates and cryptographic keys. They also develop tools for generating ransomware-obfuscated variants. A BSI report30 identified an average of 250,000 new variants per day. For example, the LockBit group has released different versions of LockBit ransomware, and the latest version, LockBit 3.0, came out with the message: “Make Ransomware Great Again!” At the same time, the LockBit group innovated by announcing a bug bounty program. And in a baffling interview at The Record, a representative from the BlackCat group advertised its products.

RaaS operators provide leak sites, the so-called hall of shame, to show an excerpt of the exfiltrated data using an onion domain so that the victim can learn more about what has been stolen. This name-and-shame stratagem is also an additional means of putting pressure on victims by damaging their reputations. Negotiation services, which are also supplied to communicate with victims, are also offered or are outsourced by other threat actors, such as chat facilities33 and even call centers, which might be used to threaten victims. Negotiations can last a long time for a large company, and just like in the used-car market, the price may be negotiated down, in line with the victim’s financial capacity,22 or even up!

The last step involves laundering the revenues. Each group and threat actor has different money laundering strategies,26 using exchanges and mixers. Law enforcement agencies can sometimes identify threat actors from cryptocurrency transactions. In rare cases, law enforcement agencies can retrieve the payment made by the victim. Coordinated international law enforcement actions are also essential to take down illicit online marketplaces and laundering services. For instance, the cryptocurrency platform Bitzlato, involved in more than US$15 million of ransomware proceeds, was seized in January 2023. Another example is the darknet cryptocurrency “mixing” service ChipMixer, which had laundered US$3 billion worth of cryptocurrency since 2017, including proceeds from ransomware activities. In March 2023, ChipMixer was taken down in a coordinated action from police forces in several countries.

RaaS infrastructures are made up of what is known as “grey infrastructures”—that is, bulletproof servers located in countries that do not usually cooperate with international law enforcement agencies. Grey infrastructure is used to operate services including virtual private network (VPN) and cryptocurrency exchanges, a “safe haven” for criminals. Sometimes, legitimate services are inadvertently abused. As such, it is quite common that payloads are downloaded from cloud services.

A resilient underground economy. The RaaS model has several advantages for criminal activities. Firstly, the model makes it possible to capitalize on know-how by sharing tools, infrastructure, and manuals (a sly reference, one such gang is named “Read The Manual”). Thus, professional threat actors sit alongside low-tech actors, and they communicate with each other.38 Shared information encompasses enterprise targeting and knowledge of system administration and security misconfigurations.

Different groups cooperate to provide various specialized services, such as Internet access brokers (IABs) and negotiation services.20 Dark markets complete the overall picture. For example, the Genesis market offered access credentials for 80 million accounts obtained during data breaches.

Moreover, the RaaS model reduces the risks as noted in Europol’s “Internet Organised Crime Threat Assessment (IOCTA) 2023” report.16 Despite coordinated international law enforcement efforts, catching lone criminals is not sufficient to dismantle criminal organizations. Affiliates are proxies that protect the core threat group. Dubbed the “world’s most dangerous malware,” Emotet was disrupted in January 2021. Less than a year later, the Emotet botnet struck back, pushing high volumes of malspam. Similarly, threat groups such as Conti have disappeared and re-emerged rebranded as several new groups.

This observation, pessimistic at first glance,26 should not hide the fact that these international actions, like operation ENDGAME, disrupt networks hosting cybercriminal activities. For instance, coordinated international actions14 led to the takedown of ransomware such as Lockbit and the seizure of botnets such as 911 S5 in 2024. The offensive action on Hive, which involved hacking the ransomware, made it possible to dismantle the infrastructure.

It can also be surmised that RaaS probably reduces costs to increase return on investment (ROI). The RaaS underground economy is based on digital markets on the Dark Web using Tor, where payment is made in cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin. Based on the studies cited in Howell and Maimon11 on information gathered from Sept. 1, 2020 to Apr. 30, 2021, the overall amount of stolen data transactions was around US$140 million in eight months, with around 600,000 sales recorded across 30 marketplaces. On average, a ransomware is sold for US$56 according to the study12 conducted from November 2022 to February 2023. It is also commonly observed that dark marketplaces flourish and are highly volatile and fragmented. The scattered nature of dark markets allows them to maintain and continue their commercial activities16 even after large-scale seizure of illegal Dark Web marketplaces, such as Dark-Market and Hydra Market, and as testified by the reemergence of the Russian Anonymous Market Place (RAMP) forum.

Ransomware Lifecycle

A ransomware campaign is mostly human-orchestrated, and it can last from a couple of hours to several months. The ransomware campaign lifecycle usually comprises five tactical stages (see Figure 2): (0) underground intelligence, (1) initial access, (2) deployment of the attack, (3) exploitation of the attack, and lastly (4) extortion. The deployment of a ransomware campaign relies on underground infrastructure. Each step requires specific techniques and procedures.

To assist in our understanding of attack processes, it is essential to have a typology. For this article, we will rely mostly on MITRE ATT&CK,a which provides a classification, organized as a matrix, of all tactics, techniques, and procedures, and which will allow us to cover each stage of the ransomware lifecycle. Tactics are the goals, such as the objective of the initial access; techniques are actions carried out to achieve a goal, such as credentials stolen to obtain remote access. The procedures used will also be scrutinized where relevant.

Stage 0: Underground intelligence service and reconnaissance. In Aug. 2021, an unhappy customer of Conti ransomware services posted an 81MB archive file named Maнyaли для paбoтяг и coфт.rar (Operating manuals and software.rar). The leaks exposed the existence of an “open-source intelligence (OSINT) team” that collects data and chats about potential targets. Thus, income, organizational, and location data is gathered to select the intended targets and avoid others—for example, to stay undercover. The reconnaissance phase is not limited to just the Underground Intelligence Service and should be understood as an integral part of the ransomware ecosystem. Indeed, IABs are key cyber actors that sell access to threat actors. This includes Web access, authentication cookies, and VPN credentials to impersonate users. Stolen data comes from a compromised mailbox, a cloud drive, or other accessible cloud resources. Credentials are obtained by various means, notably by credential phishing attacks and infostealer and ransomware campaigns. Infostealer campaigns operated in particular by traffers play an important role and are a thriving underground economy—for example, using Redline Stealer for 120€ by month.16

While it is virtually impossible to know the true number of leaked and operational credentials available in underground markets, this stolen information is a potential initial access vector. Verizon’s report8 on data breaches states that more than 50% of data breaches are due to stolen credentials.

As can be seen, the overall picture drawn is of an underground intelligence service that carries out reconnaissance and gathers information and credentials, selling them through IABs using ransomware ecosystem infrastructures. As a result, ransomware groups may target victims and have quick access to enterprise networks.

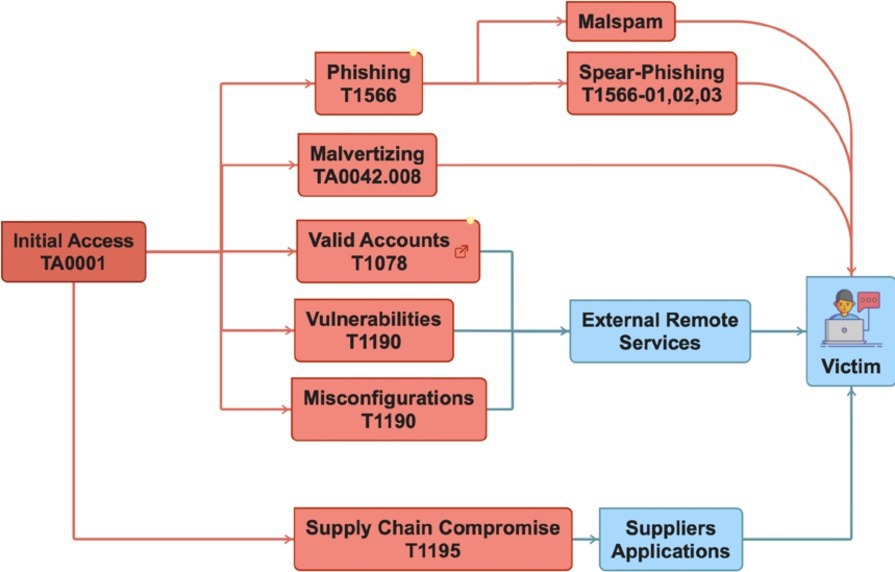

Stage 1: Initial access. It is difficult to determine the initial foothold and the technique used. According to the ENISA report on ransomware,25 in 2022, “Out of the 623 incidents studied, it was not reported how the threat actors gained initial access in 594 of them, which represents an overwhelming 95.3%.” This is the case even though most states require organizations to report any cyber incident they experience.

Despite the lack of data, phishing, access using valid accounts, misconfigurations, vulnerability exploitations, and supply-chain compromises seem to be the four most prevalent initial vectors of ransomware campaigns. The initial footstep is evidently the main step of a ransomware campaign. Moreover, it is crucial to consider the human factor, prey to social engineering attacks and prone to misconfigurations and mistakes. This is one reason why education is so important.

Phish and clicks. While it is as old as humanity, social engineering plays a key role in hacking humans. Social engineering relies on deception, or trickery, to gain the trust or interest of a potential victim—for example by posing as a close friend, colleague, or superior. In this way, the victim unknowingly hands over access to a system.

A large-scale spam campaign, malspam (a contraction of malware and spam), is a typical untargeted phishing attack. Botnets are used to distribute emails, which may contain a corrupt file, such as a PDF, an MS Office file, or a link to an attacker-controlled online file-hosting solution. Various tactics are used to hide the payload links to bypass email filtering technologies.

While some ransomware delivery campaigns via massive spam phishing are unsophisticated, phishing campaigns can be rather perceptive, using a mixture of social engineering cues. For this, a targeted form of phishing, known as spear-phishing, is commonly used. Business email compromise (BEC) is a good illustration of deceptive and widely used spear-phishing. Threat Analysis Group (TAG)32 reports elaborate strategies of an IAB with ties to Conti and probably related to a cybercrime gang known as FIN12. In this campaign, it is estimated that more than 5,000 emails a day were sent targeting around 650 organizations. The group spoofs organizations and identities, creates fake personas, and impersonates real company employees. In the final stage, a payload is uploaded via a public file-sharing service, such as WeTransfer or OneDrive. Another example is the IcedID loader, which uses a legitimate-looking contact form to send a victim an email. The email attempts to threaten the victim to force them to click a link, which results in downloading a malicious ZIP file and executing Conti ransomware.

Malvertising is yet another phishing scam that hijacks online advertising platforms, such as Google ads,30 by, for example, search engine optimization (SEO) poisoning to alter rank sites in search results. The corrupted links will then direct the victim to a spoof domain, which will be a bogus Web page similar to the one expected by the victim. Victims think they are downloading legal software when in fact they are downloading malware. It is fairly safe to predict that social engineering, playing on cognitive biases, will become increasingly credible and targeted as it is designed by AI tools capable of creating a perfect illusion and thus continue to be an important initial access vector.16

Opening the door with compromised credentials. In various access scenarios, valid credentials previously stolen or bought by threat actors have been directly used. Multi-factor authentication, such as 2FA, can be bypassed through phone-based social engineering (vishing) or SIM-swapping. According to the hearing at the House Committee on Homeland Security,6 initial access to the Colonial Pipeline system came from a reused password to access a VPN service. Similarly, LockBit hacked and stole passenger information data from airline company Bangkok Airways. According to a KELA report, access to Bangkok Airways’ VPN was sold in an auction a month before the attack. In addition, noisy, brute-force attacks of credentials are another common way to open system doors. The Akira ransomware is accustomed to using compromised credentials, either obtained from IABs on the Dark Web or through brute-force attacks, sometimes combined with vulnerability exploitation.

One reason this tactic works is users tend to reuse passwords, and generally speaking, they have a hard time understanding cyber risk.

Vulnerability exploitation. In the golden age of computers, gaining access to a system by exploiting a vulnerability was a feat that gave hackers “hero” status in cyberworlds. But times have changed, as illustrated by the massive WannaCry attacks on May 12, 2017 that smashed high-profile systems—including Britain’s National Health Service (NHS)—with a cost estimated at around US$4 billion in damages. The initial vector was WannaCry, the EternalBlue exploit, and the DoublePulsar backdoor based on CVE-2017-0144, a vulnerability allowing remote attackers to execute arbitrary code on unpatched Windows Server Message Block (SMB) computer networks. This is not a zero-day vulnerability per se. Indeed, according to several sources, the exploit was allegedly developed by the NSA,24 leaked by the Shadow Brokers hacker group in April 2017, and Microsoft had released a patch a month before the attack. The same exploit was again used during the NotPetya cyberattack on not-yet-patched computers.

The WannaCry story illustrates the use of vulnerabilities allowing remote code execution (RCE) against public-facing Internet services such as network file-sharing protocols (SMB, FTP), remote desktop protocols (RDP), and VPN.

The exploitation of vulnerabilities is on the rise. Cyberthreat actors now can develop attacks after a vulnerability is identified, even using zero-day exploits, as demonstrated by Cl0p’s attack on MoveIt software.32 CISA provides an annual list of “Top Routinely Exploited Vulnerabilities,” more than two-thirds of which were related to RCE and associated with ransomware attacks in 2023. Publicly disclosed vulnerabilities are listed as common vulnerabilities and exposures (CVE). The Common Vulnerability Scoring System (CVSS) evaluates the threat level.

A ready observation is that it is difficult to list and update vulnerable or misconfigured assets even if the exploit is known and patches have been already released. One reason for this is the complexity of systems and their interdependencies, in that several months after a CVE disclosure, many applications remain vulnerable, sometimes for a long time.

Microsoft Exchange Server has been plagued by a series of vulnerabilities—ProxyShell, ProxyLogon, and ProxyNoShell—allowing attackers to remotely execute arbitrary code and commands, and to gain unauthorized access to a system. A combination of several vulnerabilities are used in different ways to form a single attack chain.10 In the end, a common foothold is the installation of a backdoor, a Web shell such as PowerShell, allowing execution commands on the victim’s server. For example, although Microsoft released patches on May 11, 2021, ProxyShell was exploited repeatedly by ransomware such as Lockfile, Conti, and Hive—all long after Microsoft’s correction. Similarly, several network appliances, such as VPNs, were targeted by cyber threat actors by exploiting vulnerabilities. For example, the Akira ransomware leveraged a zero-day vulnerability in a CISCO appliance that allowed unauthenticated remote access.

Open source codes also contain flaws. The zero-day exploit Log4Shell19 is based on several vulnerabilities in the open source, Java-based logging framework Log4j. Log4Shell is a simply crafted string request to allow the execution of arbitrary code and to take full control over a system. Log4j has highlighted the fact that a pervasive library is difficult to update due to complex software dependencies.

Lastly, VMware’s ESXi is a bare metal hypervisor that hosts virtual machines and is widely used all over the world. As a result, an attack on ESXi hypervisors allows access to be gained to virtual machines and their storage: It is the goose that lays the golden egg. That is why VMware’s ESXi hypervisor has become a popular target for ransomware,37 such as LockBit, Hive, Babuk, and ESXiArgs.

Supply chain. The last access vector to be examined is the one that uses supply-chain layers. A supply-chain attack is a two-stage attack (See Figure 4). First, a supplier is compromised using one of the aforementioned procedures. When the compromised supplier application or service is distributed to a client, it is in turn compromised: an attack by transitivity. Supply-chain attacks are sophisticated but also attractive because they multiply the number of victims. A prime example is the supply-chain attack carried out against SolarWinds in December 2020, where it was claimed that the U.S. Departments of Homeland Security, Commerce, and Treasury had all been hacked. In July 2021, a supply-chain attack against Kaseya IT management software delivered ransomware, this time attributed to the Revil group. Another example, slightly different, is the compromise of MoveIt by the Cl0p,32 a widely used file-transfer software, which led to significant data breaches affecting numerous organizations.

The complexity of IT/OT systems, relying extensively on applications and services provided by suppliers and embarking third-party APIs as well as open source libraries, offers a broad attack surface. Each software component has privileged access or stores sensitive data. The entire IT system becomes difficult to control from end to end, is prone to errors and misconfigurations, and is difficult to update properly. Therefore, each element of this system is a potential security flaw. In this sense, the Log4j-related compromises perfectly illustrate the challenges and the issues.

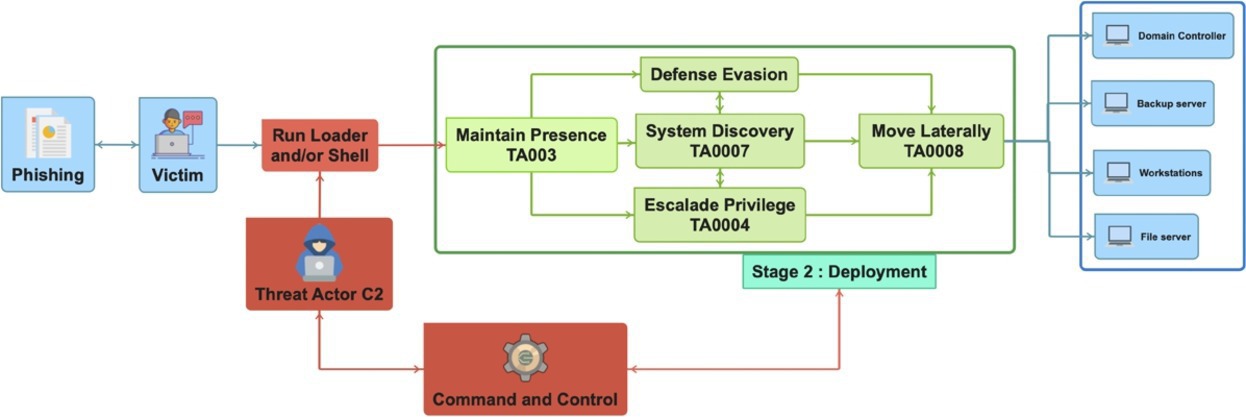

Stage 2: Deploying ransomware campaigns. The initial footstep will trigger a sequence of actions executed by script, macro, or binary code, usually called malware loaders. Typically, a loader will try to establish a communication between the threat actors and the compromised system, which becomes a bot. The bot will carry out the commands of the threat actor command and control (C2) servers, and C2 may then receive exfiltrated information from the bot. The communication is made through covert channels, combined with legitimate traffic. The primary goal of a loader is to download and execute additional payloads and to deploy human-operated ransomware. For example, the loader Bumblebee is distributed by an email with an attachment containing an ISO file with a malicious DLL, which will deploy the Quantum ransomware as a payload at the end of the attack.

Then, ransomware campaigns are essentially human-operated attacks. Depending on the perpetrator’s skills and the initial access vector, this means there is variation in the plan of action depending on the environment, opportunities, and objectives of the threat actors. Despite disparities in tactics, the deployment can be summarized into five main steps: maintaining presence, escalating privileges, taking defensive/evasive action, credential access and discovery, and moving laterally. A vital issue for the threat actor is to stay undetected. Hence, a lot of threat actors “live off the land” using and installing legitimate software rather than noisy tools, such as post-intrusion Cobalt Strike, Sliver, or homemade tools.

Maintaining presence. Attackers must maintain their presence by installing backdoors while remaining undercover. Since threat actors may now interact with the compromised system, a widespread tactic is to run legitimate services and legitimate commands such, as PsExec (light-weight telnet) or PowerShell scripts as in a LockBit9 campaign. The presence of backdoors and rootkits is assured over time by, for example, creating a scheduled task. Another common technique is to create new user accounts to grant extra remote accesses.

Escalating privileges. Attackers often escalate privileges by bypassing the system access-control mechanisms, typically Windows User Account Control (UAC). The goal is to get more access privileges and ultimately get a root privilege. Privilege escalation may be carried out using stolen credentials, as it is done by BlackCat,33 or by a brute-force attack. Again, publicly available tools such as Mimikatz and MiniDump are commonly used to dump credentials to escalate privileges as exemplified by LockBit.9 Another way to gain administrator rights is to exploit vulnerabilities. For example, the loader Qakbot leveraged Zerologon vulnerability to gain administrator privileges to later enable it to deploy several ransomware programs, such as Conti and Black Basta.26 In August 2023, a large Qakbot botnet was dismantled, seizing $8.6 million in cryptocurrency and 700,000 compromised computers worldwide.

Taking defensive evasion. To carry out their misdeeds, it is necessary for threat actors to hide malicious actions and payloads, as they need to stay unnoticed. This means the overall behaviors of the compromised system should remain normal, and dropped files should look similar enough not to be detected even by a machine learning engine.

Defense mechanisms such as anti-viruses, endpoint detection and response (EDR) sensors, and cloud monitoring agents are disabled as exemplified again by Black Basta26 to avoid the attention of incident responders or Security Operations Centers (SOCs).

Executed scripts and binary programs are also disguised by obfuscation methods. For example, executed commands are concealed by using hidden windows or encrypted command lines, such as Hive using base64-encoded PowerShellcommands. The Bumblebee loader uses control-flow-flattening obfuscation. Version 2 of Conti implements API hashing and version 3.0 of LockBit implements function-call trampoline to hide API and internal function calls. Another rather common obfuscation is to inject a code into running processes, such as IcedID that tampers with Winlogon and Explorer processes. Packers are also widely used to hide a payload. In this case, execution unfolds in a sequence of waves of code, with each wave unpacked and run on the fly.

Credential access and discovery. To pivot laterally, it is necessary to map the victim environment and gather information such as domain names, users, and hosts, and to steal credentials such as passwords that will be exfiltrated at a later stage. From there, a threat actor should be able to proceed to a lateral move by gaining access to remote systems or file-sharing services.

System discovery can be performed by legitimate system commands and tools, such as AdFind, that collect information from the Active Directory. Credentials are extracted with tools such as Mimikatz in LockBit campaigns12 or, as in Vice Society27 campaigns, leveraging the Local Security Authority Server Service (LSASS).

In all cases, tools for penetration testing are used, whether they are legitimate or homemade; in particular, “Swiss Army Knife”-like tools Cobalt Strike and Metasploit are quite often deployed. These tactics and procedures are shared by loaders and ransomware, and good overviews are given typically by Vice Society ransomware.27

Move laterally. Once the first stage of the attack is deployed, threat actors frequently move laterally within a network using remote access services, such as Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP), or through network file-sharing services, such as Server Message Block protocol. These new doors enable the attack to spread by deploying additional tools and payloads on other targets. As already explained, threat actors use previously stolen valid credentials or merely take advantage of security misconfigurations, sometimes with administrative privileges to pivot. As a result, the initial attack moves and morphs into a multi-front attack that may install new backdoors and thus pursue the incursion.

Stage 3: Exploitation.

Data exfiltration. Prior to the ransom demand, threat actors exfiltrate most specific file types from several selected directories, and in addition sometimes do not even encrypt the system. To this end, data is transferred using File Transfer Protocol (FTP) services or tools such as Rclone or MegaSync and compressed typically with 7zip. Other threat actors prefer to use custom data exfiltration tools, such as StealBit or Exmatter, a .NET executable compiled with Themida, an anti-reverse-engineering software-protection utility. These tools show once again the ability of threat actors to develop and maintain software.

Data encryption. There are several tactics to lock a system. All files, or just certain kinds of files, are encrypted and backups are deleted. However, it can happen that only key information on a system, like partition tables or just file headers, is corrupted. In all cases, data encryption is hybrid, combining asymmetric encryption and symmetric encryption. In a nutshell, let be the file encrypted with the symmetric key . Then, the attacker generates a pair of public and private keys on the victim host that will be used to protect a symmetric key. The symmetric key is encrypted and the private key, which is necessary to recover the symmetric key , is encrypted with the attacker public key . The symmetric encryption utilizes stream ciphers such as AES256 (Royal30), ChaCha8 (Babuk), ChaCha20-Poly1305 (Vice Society) and Sosemanuk (ESXiArgs). The asymmetric encryption utilizes RSA (Royal30), NTRUEncrypt (Vice Society) and Elliptic-curve Diffie-Hellman (ECDH) (Babuk) algorithms.

Symmetric encryption is used because it allows the fast encryption of large files. Efficiency is key to avoid detection and hence why ransomware such as Lockfile, Royal,30 and Vice Society use intermittent encryption, which consists of encrypting only part of the file. Another ransomware tactic to speed up encryption is to use multithreading symmetric data encryption. A further issue is the entropy of the encrypted file, which needs to stay low to conceal the encryption process from defense monitoring.

Stage 4: Negotiation and extortion. To get a ransom or to be paid in one way or another is crucial for the threat actor. Today, the double extortion strategy of data exfiltration and date encryption is a commonplace occurrence. Some threat actors may even offer a 24/7 help desk to victims. The ransom negotiation22 is generally private, but a few ransom chats are available.20 Since data tends to be exfiltrated, cybercriminals may threaten the victim with the public release of stolen information or inform the victim’s partners of the incident. Victims can browse leak sites to check the extent of stolen data, and the threat actor may pressure victims to pay the ransom. Cyberthreat actors may directly threaten victims through phone calls or emails. In 2023, the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center in Seattle was hit by a ransomware attack, during which cancer patients received intimidating emails. The Royal group has threatened23 to release the personal information of Dallas employees, including police and justice information.

This means of extortion is convincing enough that some groups threatened to publish stolen data without having first encrypted it. Cl0p exploited several zero-day vulnerabilities from the MoveIt transfer application32 to exfiltrate data—without locking files—from about 70 million individuals. Thus, hundreds of gigabytes of data may be stolen, with British Airways, the BBC, and Transport for London, among others, as victims.

If negotiations fail, threats are sometimes carried out. For example, following the 2023 MSI data breach, firmware keys were publicly disclosed on the Dark Web, compromising the integrity of a number of firmwares. In September 2023, several Las Vegas casinos experienced data breaches attributed to BlackCat. Initial access was reportedly gained through employee impersonation. After negotiations seemingly failed, the attackers launched ESXi hypervisor encryption.

Even if the victim pays the ransom, there is no reason for cybercriminals not to sell stolen information. In rare cases, these threat actors may escalate by adding a DDoS attack if the victim does not comply with the ransom demand. This triple-extortion strategy is practiced by, for example, BlackCat.33

Victimology, Cost, and Revenue

The damage caused to an organization by ransomware incidents can be divided into internal damage to restart the organization (restoring systems and any remediation services), external damage (lost business due to inability to operate), and reputational damage. The Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3)15 reports that there were 2,825 ransomware complaints with losses of more than US$59.6 million in 2023, and ransomware attacks are ranked only 20, far behind phishing and data breaches, both in terms of number of complaints and financial losses. At the same time, IC3, as well as reports from various states,7,25,34 cautions the reader that these losses are likely to be underestimated due to a lack of information. When Netwalker was dismantled, the FBI claimed that less than 25% of incidents were reported. On the other hand, a survey34 of Sophos clients (out of 5,000 respondents representing organizations with between 100 and 5,000 employees) estimates that the average recovery cost was US$2.7 million in 2024, which more or less corresponds to other company report estimations, representing an increase of nearly 50% over the past three years. It is difficult to accurately estimate losses caused by ransomware. As already mentioned in the introduction, there is a lack of reliable data on ransomware incidents.36

It is the same for ransom payments and criminal revenues. In 2022, ENISA25 suspects that around 60% of victims have paid the ransom despite the fact that most governments caution against paying a ransom. A Sophos survey34 on 1,097 respondents reports a median ransom payment of US$2M in 2024. On the other hand, an independent study28 found that the median payment value is US$1,176. These significant variations show that, depending on criminal behavior, the type of victims, and their income, ransom demands can vary greatly, which once again highlights the lack of consolidated information. In addition to these figures, the FBI states that Hive ransomware actors received approximately US$100 million in ransom payments. It appears that the Dark Angels ransomware group received a record $75 million ransom payment from a pharmaceutical company, which was considered a record in 2024.

Cyberinsurance39 may be viewed as a risk mitigation tool to assist companies during a ransomware crisis. Insurance companies require policyholders to provide a certain level of security for their system. However, cyberinsurance appears to make certain companies, paradoxically, less vigilant regarding legal obligations related to data privacy and service availability.

Conclusion

Today’s IT/OT systems are complex, built on intertwined infrastructure, interdependent, and consequently increasingly difficult to control. The result is a favorable ground for cybercriminals, particularly ransomware, whose main motivation is financial. The methods of operation have naturally evolved and gained maturity. Underground organizations are taking shape, sometimes instrumentalized by states, as the Ukrainian conflict has shown. This is hardly surprising, given that the means of a cyberattack are virtually the same whether the objective is financial, espionage, or destruction.

Despite its resemblance to the ransomware WannaCry, NoPetya’s actions were destructive, causing approximatively US$10 billion in total damages, and in a way, prefiguring cyberattacks during the Ukrainian conflict13 using wiper weapons. Geopolitical tensions could encourage actors behind ransomware to perpetuate ongoing cyber conflicts, becoming sources of intelligence and easily adapting their behavior. Inversely and as illustrated by state advanced persistent threat (APT) groups, ransomware techniques maybe used either to conceal an objective behind a criminal mask or to obtain cryptocurrencies. However, newspaper headlines about high-profile attacks should not overshadow the harsh reality on the ground, which is purely criminal, indiscriminately targeting individuals, hospitals, schools, and all vulnerable organizations and businesses.

Anticipating the next move of a ransomware group could be crucial. For instance, it is not hard to imagine new methods of extortion and harassment designed to ensure payment. Instead of merely encrypting data, threat actors might modify it, a prospect that becomes particularly alarming in a hospital context. They could also intensify pressure by hijacking their victim’s social networks, potentially using advanced AI chatbots, thereby affecting the victim’s public relations and reputation. That said, initial access is always a key step in a cyber-threat campaign. That is why, beyond the publication of guidelines on cybersecurity by states, education is so important. Indeed, humans are not prepared to face cyber-threats and are all too often the unintended key vector for opening doors to IT/OT systems. The exploitation of vulnerabilities and supply-chain attacks is also an important issue. There needs to be a collective reflection on the design of infrastructure where security is considered an essential element: security-by-design. One way to ensure this is to perhaps develop regulations and legislation at the international level. Progress has been made in this sense with, for example, the software bill of materials (SBOM) executive order 14028 to improve the U.S. cybersecurity order adopted in 2021 and the new Network and Information System Security (NIS 2) directive adopted by the European Parliament in 2022. These directives make it possible to impose security measures on companies, thereby reducing the risks associated with software supply chains and IT/OT infrastructure.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by a government grant managed by the French National Research Agency (ANR) as part of France 2030 under reference “ANR-22-PECY-0007”. Figures have been designed using icons from Flaticon.com created by Paul J.

Join the Discussion (0)

Become a Member or Sign In to Post a Comment